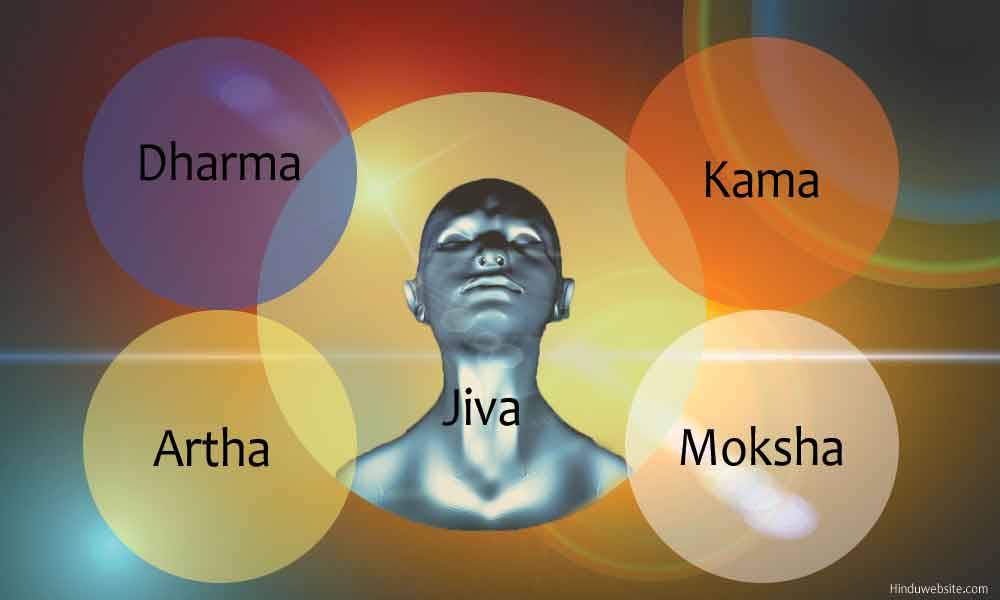

101 Law,154,British Law,3,Constitutional Law,16,Contract Law,18,Equity and Trust Law,7,Hindu Law,15,Jurisprudence,16,Labour Law,5,Law of Limitation,1,Legal Terms,3. Family Law / Hindu Law – UNIT I — Revision Study Notes for LL.B Introduction of the Hindu Law Concept of Dharma Hindu Law is a body of principles or rules called ‘Dharma’. Dharma according to Hindu texts embraces everything in life. According to the Hindus, ‘Dharma’ includes not only what is known as law Continue reading Class Notes on Family Law/Hindu Law 1 – UNIT I (1st Sem.

Sir William Jones and the translation of law in India

What happens when you translate a legal system from the metropolitan imperial centre to a colony? The case of Sir William Jones provides one instructive answer.

Sir William Jones (1746–94) is an unusual figure in that he worked directly within the fields of literature and law: he was both poet and lawyer (he is credited with the invention of the concept of ‘the reasonable man’ in his Essay on Bailments (1781) (Oldham 1995)), translator (notably in his own day of the Persian poet Hafiz), judge and jurist, and a central figure in the development of English law in India. Jones’ interdisciplinary talent and professional energies are one reason why his work has remained hard to assess within any of the individual fields in which he worked. Even within the two fields of literature and law individually considered, his work was generally comparative – before the subjects of comparative literature or the historical and comparative school of legal philosophy had been invented. He was also a historian, and of course a linguist, or more properly a philologist – indeed he is customarily credited with the invention of historical or comparative philology as a discipline in Britain, and it is in this context that in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries he has been most regularly cited (Momma 1997). He was not the first to recognize the affinities between Latin, Greek and Sanskrit, but it was Jones who suggested that, together with Gothic, Celtic, and Old Persian, they were related languages genealogically derived from a common root – a language that in 1813 Thomas Young would name Indo-European (albeit in a different and more eccentric genealogical configuration).

Jones’ own remarkable talent for languages, and relatively unusually for his time and for ours, non-European languages – meant that by the end of his life he knew English, Latin, Greek, French, Arabic, Hebrew, Turkish, Persian, Sanskrit. His famous writings on the comparative historical relations between those languages notwithstanding, as a good utilitarian, his view of language was always instrumental: as he put it in the Introduction to his translation of Al Sira-jiyyah: or, the Mohammedan Law of Inheritance ‘practical utility being my ultimate object in this work – it has nothing to do with literary curiosities’ (Jones 1792: iv). He did not regard knowledge of languages as learning in its own right; rather it formed the means to learning. And the learning that each language contained he considered always translatable into another language. His work is founded on a deep principle of translatability, of equivalence between languages. While he believed in linguistic translatability, paradoxically the whole rationale of his legal work was at the same time founded on a principle of cultural untranslat-ability. This, however, did not prevent a profound cultural translation from taking place.

Hindu Law: Texts And Materials Homework

Jones begins the Preface to The Laws of Menu with two sentences that take up a page apiece. In the first, he writes:

It is a maxim in the science of legislation and government, that Laws are of no avail without manners, or, to explain the sentence more fully, that the best intended legislative provisions would have no beneficial effect even at first, and none at all in a short course of time, unless they were congenial to the disposition and habits, to the religious prejudices, and approved immemorial usages, of the people, for whom they were enacted; especially if that people universally and sincerely believed, that all their ancient usages and established rules of conduct had the sanction of an actual revelation from heaven: the legislature of Britain having shown, in compliance with this maxim, an intention to leave the natives of these Indian provinces in possession of their own Laws, at least on the titles of contracts and inheritances, we may humbly presume, that all future provisions, for the administration of justice and government in India, will be conformable, as far as the natives are affected by them, to the manners and opinions of the natives themselves; an object, which cannot possibly be obtained, until those manners and opinions can be fully and accurately known.

Hindu Law: Texts And Materials Homemade

These are the main considerations, Jones writes, which have led him to translate the Laws of Menu, ‘a system so comprehensive and so minutely exact, that it may be considered as the Institutes of Hindu Law’ – a remark that transforms the identity of Menu at a stroke into the systematic form of a European legal text (Brine 2010). Even though Jones considers Menu to consist of the ‘institutes’ of Hindu law, he nevertheless expresses the wish for the law to be systematized further, beyond Halhed’s Digest, it being, he suggests: